Key symptoms of depression related to a risk assessment

In real terms depression is merely a collection of symptoms, it is not so much that depression is linked to suicide it just happens that people who are suicidal have symptoms which are not uncommon in depressed people as well. In using this measure in a suicide risk assessment one does not enquire about depression per se but one enquires about some of the symptoms found in the depression that the person is displaying.

The DSM-IV provides a list of symptoms which define depression, these being:

1. Depressed mood most of the day which can include a sense of hopelessness.

2. Loss of interest or pleasure (in all or most activities, most of the day).

3. Large increases or decreases in appetite (significant weight loss or gain).

4. Insomnia or excessive sleeping (hypersomnia).

5. Restlessness as evident by hand wringing and similar other activities (psychomotor

agitation) or slowness of movement (psychomotor retardation).

6. Fatigue or loss of energy.

7. Feelings of worthlessness, or excessive or inappropriate guilt.

8. Diminished ability to concentrate or indecisiveness.

9. Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide.

Taken from, American Psychiatric Association (1994).

In this diagnostic system one needs to have five or more of these symptoms to be diagnosed as depressed. Thus every suicidal person automatically has one symptom of depression already as shown in symptom number nine. The best clinical predictors of suicide in depressed people include previous self-harm, hopelessness and suicidal tendencies. (Beck, Steer, Kovacs and Garrison (1985) and Beck, Brown and Steer (1989) both found hopelessness to be one of the best indicators of suicide risk). If the depressed person reports a loss of appetite, psychomotor agitation, excessive guilt, hypersomnia and increased indecisiveness then they meet the criteria of depression but show none of the best clinical indicators just described. Indeed unless the depressed individual reports the last symptom, recurrent thoughts of death and suicide, it seems safe to say that the person is not a suicide risk at this time. They are not even thinking about suicide at this point even if they have all eight other symptoms of depression. If a person presents as depressed one firstly asks if they have the symptom of thoughts of suicide and if they do then one also enquires about a sense of hopelessness and any previous self harm. If they present with all three one is getting a much more accurate assessment of the current level of risk.

In the literature one finds very little research on the number of people who report depression and who report no recurrent suicidal thoughts. One has to search long and hard and three such research studies were found. The first from many years ago by the 'father' of depression, Arraon Beck (1967). He presented research results which examined the presence of suicidal wishes in the depressed person. He makes the distinction between neurotic depression or the milder forms of depression and psychotic depression or the more severe forms of depression. (This distinction will be discussed more later in this chapter). The results were:

Mild or moderate level of suicidal wishes present:

Neurotic depression - 58%

Psychotic depression - 76%

Severe level of suicidal wishes present:

Neurotic depression - 14%

Psychotic depression - 40%

More contemporary research by Akechi, Okamura, Kugaya, Nakano, et al (2000) reports that in patients with major depression fifty three percent had suicidal ideation. Wada, Murao, Hikasa, Ota, et al. (1998) also report a similar finding of around fifty percent of those with major depression having suicidal urges as well. This allows the conclusion that about fifty percent of those with some form of depression do not report any recurrent suicidal thoughts. Thus it seems safe to say that fifty percent of depressed people are not at risk of suicide as they are not even thinking about suicide let alone planning anything.

Timing of the depressive episodes

If the individual does present as depressed and does show the principle signs of recurrent suicidal thoughts, a sense of hopelessness and previous self harm then of course this is an important factor in the risk assessment and definitely requires more investigation. One of the more important aspects to investigate is the course and stage of the depression. As stated by the Bayley (2004) depressive episodes can be single, recurrent or chronic and this has significant implications for the assessment and management of the suicidal individual.

For about five to ten percent of depression sufferers the depression is chronic. If an individual with chronic depression also has recurrent thoughts of suicide then the level of risk increases and over time it could be seen as continuing to increase. In the longer term this person could be seen as quite a significant suicide risk. One would to be questioning the individual as to their feelings about tiring of life and particularly a sense of hopelessness. These individuals have a poor quality of life with the spirit crushing depression and often quite unpleasant side effects from the medication like obesity, lack of energy and so forth. If they have tried just about every type of medical and psychological treatment with little improvement one would be assessing a definite increase in the risk of suicide.

To make matters worse there is not much one can do in their management. A no suicide contract is of less use as there is no end in sight for the depression. As the suicide risk increases over time one can place them in hospital or on some kind of suicide watch but what does that achieve? It simply relocates them geographically and how long does one keep such a person in hospital as they will be depressed upon release.

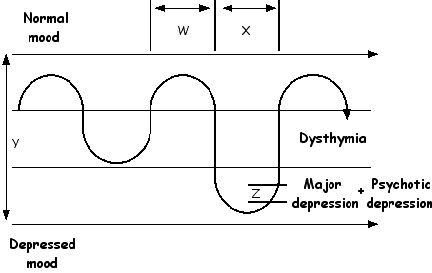

However for most depression is cyclical as is shown in diagram 4 with the mood changing over time from a normal level to a depressed level and back.

Diagram 4

The cycles of depression

As stated in the Bayley (2004) the rate of recurrence of depressive episodes is quite high, "50% of people who have had one episode of depression will relapse, 70% of people who have had 2 episodes will relapse, and 90% of people who have had 3 episodes will relapse"(p159). The average duration of an untreated episode is about twenty to twenty six weeks but many can have much briefer episodes of around four to six weeks. If treatment is obtained early then the duration and severity of the episode may be significantly reduced.

Types of depression

In using depression as a measure to assess suicide risk one needs to distinguish a number of different types of depression. As is shown in diagram 4 one can move from a normal mood range into the range of dsythymia. In this phase the depressive symptoms are at a moderate degree. Historically this has also been known as neurotic depression and I use the terms interchangeably. This is seen as less severe than the next level which is called a major depression. In this phase the depression symptoms are at a severe degree. Sometimes this is called 'clinical depression' and the individual is significantly incapacitated and is very depressed. Also at this level one can have a condition known as psychotic depression. This is where the individual has the symptoms of major depression plus some psychotic symptoms. This terminology has been around for many years and psychotic depression is well summarized by Beck (1967) who says it is "...characterized as including patients who are severely depressed and who give evidence of gross misinterpretation of reality, including at times delusions and hallucinations"(p82).

In summary in this model we have:

Normal mood

Dysthymia or neurotic depression

Major depression and psychotic depression

In diagram 4 we have an individual who begins with a period of normal mood who then moves into a phase of depression that is consistent with the diagnosis of dysthymia. Eventually that depressive episode ends and he recovers again for a period of normal mood. Unfortunately at a later time he again moves into a more severe episode of a major depression which he eventually recovers from and moves back to a state of normal mood. To assist with making a suicide risk assessment one can create a graph like this for the person who complains of depressive episodes.

In assessing the depressed person one need to look at four aspects of the depressive cycle W, X, Y and Z. Firstly one is wanting to assess the length of the non depressed periods (W) and the lengths of the depressive episodes (X). Of course this relies on the person having had previous episodes and one simply takes a history of the person in this way. How many have there been and how long were they? Also were there any precipitating factors such as marital problems or financial difficulties that lead to the depressive episode. These can then be charted on a graph as is shown in diagram 4. People tend to behave in patterns and one is obtaining this information to assist in predicting future episodes and thus future times when suicidal urges may increase in conjunction with the depression. Of course future episodes may be different to past ones but this does give some guidance to assist the suicide risk assessor.

For example if there is a pattern in the timing of the episodes one then knows when approach the person for a risk assessment in the future. A good example of this is with what has become know as Seasonal Affective Disorder or SAD. Typically the depressive episode begins in autumn or winter and remits in spring. Alternatively previous depressive episodes may be related to particular events such as examination time at college or when a loved one has to travel away for work. Plotting the 'W' and 'X' of the depressive episodes will allow the risk assessor to improve the timing of their assessments.

Degree of depression and suicidality

One also needs to assess the quality of the depressive episodes by making an assessment of the 'Y' component. Here one assesses how depressed the person becomes, how the person has felt in past episodes particularly in relation to suicidal thoughts. As mentioned before the system being presented here distinguishes between normal mood, dysthymia or neurotic depression, major depression and psychotic depression.

This is an important component to distinguish in a suicide risk assessment as there is some research which concludes that those who are more depressed are more prone to suicidal thoughts. In their research on depression and suicidal thoughts Garlow, Rosenberg, Moore, Haas, et al (2007) report “These results suggest that there is a strong relationship between severity of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation in college students...”(paragrpah 1). In addition Perroud, Uher, Marusic, Rietschel, et al (2009) state “Increases in suicidal ideation were associated with depression severity...”(p2). Finally Beck (1967) cites research which shows that a severe level of suicidal thoughts were present in fourteen percent of those with neurotic depression and in forty percent of those with psychotic depression. In conclusion, the more depressed one is the higher the risk level of suicidal thoughts. Thus one can see the importance of making the 'Y' component assessment of the reported depressive episodes.

As just noted the person with major depression or psychotic depression is at more risk of suicidal thoughts than the person with dsythymia. However it seems reasonable to conclude that the person with psychotic depression is still at even more risk than the person with major depression as a psychotic depression involves a major depression plus the presence of psychotic symptoms. That is the person experiences severe depression as well as psychotic delusions and hallucinations and thus the features discussed above in point 4, "History of mental illness" become apparent as well. There is sort of doubling effect of suicide risk factors in this instance. For example the person with psychotic depression is likely to be more regressed than someone with major depression because the psychotic features result from very poor Adult ego state functioning and thus there is increased regression. In addition the psychotic is more prone to command hallucinations as well. As a result, of all the types of depression the psychotic depression is probably the one of highest risk value when making a suicide risk assessment.

Finally in diagram 4 one needs to make an assessment of 'Z' in the depressive cycle. Suicide risk may increase as the person improves particularly in a major depression or a psychotic depression. In these depressive states the person is so depressed that they become incapacitated. They are so depressed that they literally do not have the energy to think seriously of suicide or certainly making any definite planning moves. As the depressed state lifts, along with that comes an increase in energy which may bring about an increased ability to act on any self destructive wishes, as they improve one may need to be more vigilant as they reach that part of the depressive cycle.

In addition for the individual with psychotic depression as the depression lifts the psychotic symptoms may begin to subside as well. Their Adult ego state becomes more functional and thus planing a suicide attempt becomes more of a possibility. Most suicides occur in the non-florrid stages of a psychotic episode when the person is relatively free from acute symptoms. Of particular note in suicide risk assessment if the person is at one of the lower points in the depressive cycle such as at stage 'Z' and all of a sudden shows significant improvement, that may be ominous sign. They may have made the decision to kill self and are just getting organized and waiting for the right time.

Graffiti